「今のころは、山を見て、杉と桧の違いが一番分かりやすい時だ」と川上村上多古の玉井久勝さんは今年のどんど焼きで立ち話をしながら教えてくれた。「杉の木は少し茶色くなっているから。桧はまだ緑だ」と。川上村で吉野林業の仕事をしている人が多くて、このおじさんはその一人だ。山の人工林を管理する山守である玉井さんは、40年前からこの山々で働いている。僕の近所に住んでいて、地元の消防団やお祭りやほかの行事の時、僕の参加をいつも温かい笑顔で歓迎してくれた。僕は今年の3月末にこの村を出ることになったが、その前に、ずっと優しくしてくれた玉井さんと一緒に山に行きたいと思っていた。

2月上旬の曇った朝から、僕は彼と隣の山に入り、伐採の現場に同行した。「今日の木は何年生ですか?」と僕は聞いた。「ええと、約160年生かな」と彼は何げなく答えてくれた。僕らは玉井さんの仲間の二人、大辻雅夫さん、小南修二さんと一緒に、狭くて蛇行する林道をどんどん上った。木々は約30メートルほどの高さでそびえ立ち、木の影が顔や肌に寒かった。林道を30分ほど上ってから、僕らは伐採の現場に着いた。数え切れない桧の木が、山の急な斜面に密な間隔で植えられていた。

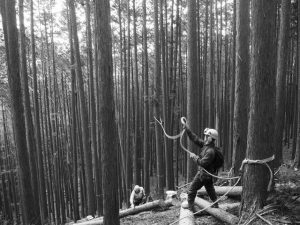

伐採の作業は木の根本付近をチェーンソーで伐り、幹をロープで引っ張り、山の上方へ倒すことだ。玉井さんはロープを桧の木に軽く結び、山の斜面を少し登ってから、ロープを一気に投げ上げた。20メートルほどのロープが波のようにしなり、ロープの輪が幹の上へと上がった。彼はロープを繰り返して投げ上げて、その輪が少しずつ上がっていって、僕らの頭より数メートル高いところに達した。大辻さんのチェーンソーの音が止まり、木が山の斜面へ傾き始めた。木の根本付近がパックリと開き、枝が隣の木と擦る音がした。葉っぱが上からぱらぱらと落ちた。ドーンと木が山に倒れ、山の隅々まで響きそうだった。

夕方まで伐採の作業を繰り返し何十回もやったけど、木が倒れた瞬間のドキドキは変わらなかった。木が圧倒的に大きくて、重いから、僕のドキドキは本能的な反応だろう。この木が人間の寿命の2倍近く長い歳月で成長してきたから、僕は木の重さと寿命の長さを考えて、人間の儚さを思い知らされた。

玉井さんたちは道具を背負い、あの長い林道を麓まで下りた。彼らは靴を履き替えてから、それぞれの軽トラックに乗った。玉井さんは窓越しにいつもの温かい笑顔を見せて、手を振って、黄昏の彼方へ帰った。

The Final Episode On the Mountain Next Door, a Day Felling Trees

“This is the time when we can look at the mountains, and it’s easy to tell the difference between cedars and cypresses,” Mr. Tamai told me, as we stood and chatted at this year’s dondo-yaki in Kodako, Kawakami Village. “The cedars have turned a little brown. The cypresses are still green.” There are many people in Kawakami Village who do work related to Yoshino Forestry, and this man is one of them. Managing forests of planted trees as a yamamori, Mr. Tamai has worked in these mountains for the past 40 years. He lives right near me, and always welcomed my participation in the local volunteer fire department, festivals, and other events with a warm smile. I would be leaving this village at the end of March, but before that, I wanted to go with Mr. Tamai into the mountains, as he had always been so kind to me.

On a cloudy morning in early February, I went with him into the mountains on a day of tree felling. “How old are these trees today?” I asked. “Hmm, about 160 years old,” he answered nonchalantly. Along with two of his friends, Mr. Masao Otsuji and Mr. Shuji Kominami, we climbed up and up the narrow, snaking forestry path. Trees soared about 30 meters high, and their shade was cold on my face and skin. After climbing the path for about 30 minutes, we arrived at the work site. Countless cypress trees were densely planted on the steep slope of the mountain.

Felling a tree involves cutting near the base of the tree with a chainsaw, then pulling the trunk with a rope so it falls up onto the slope of the mountain. Mr. Tamai tied a rope lightly around the cypress tree, climbed up the slope of the mountain a bit, and in one quick swoop, threw the rope up in the air. The 20-meter-long rope whipped like a wave, and the loop of the rope climbed up the trunk. He repeatedly threw the rope, and the loop climbed little by little, eventually reaching a point a few meters higher than all of our heads. The sound of Mr. Otsuji’s chainsaw stopped, and the tree began leaning toward the mountain slope. The base of the tree cracked open, then the sound of branches scraping the trees around it, and its leaves lightly floated down around us. The tree came falling down with a boom that seemed to reverberate all across the mountain.

They repeated this work, felling dozens of trees by early evening, but that excited nervousness I had in the moment a tree fell never changed. The trees are overwhelmingly huge and heavy, so maybe that feeling was an instinctual reaction. These trees grew to be this big in a span that was twice a human lifetime, and thinking about both the tree’s weight and the length of its life reminded me of how fragile it is to be human.

Mr. Tamai and his friends shouldered their tools, and made their way back down the long path to the base of the mountain. After changing into their shoes, they each got into their light truck. Through his window, Mr. Tamai gave me the same warm smile as always, waved to me, and drove off into the evening.